5.3 Lengthening data

5.3.1 Data in column names

billboard

#> # A tibble: 317 × 79

#> artist track date.entered wk1 wk2 wk3 wk4 wk5

#> <chr> <chr> <date> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 2 Pac Baby Don't Cry (Ke… 2000-02-26 87 82 72 77 87

#> 2 2Ge+her The Hardest Part O… 2000-09-02 91 87 92 NA NA

#> 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 2000-04-08 81 70 68 67 66

#> 4 3 Doors Down Loser 2000-10-21 76 76 72 69 67

#> 5 504 Boyz Wobble Wobble 2000-04-15 57 34 25 17 17

#> 6 98^0 Give Me Just One N… 2000-08-19 51 39 34 26 26

#> # ℹ 311 more rows

#> # ℹ 71 more variables: wk6 <dbl>, wk7 <dbl>, wk8 <dbl>, wk9 <dbl>, …billboard %>%

pivot_longer(

cols = starts_with('wk'),

names_to = 'week',

values_to = 'rank'

values_drop_na = TRUE

)colsspecifies which columns need to be pivoted, i.e. which columns aren’t variables. This argument uses the same syntax asselect()so here we could use!c(artist, track, date.entered)orstarts_with("wk").names_tonames the variable stored in the column names, we named that variableweek.values_tonames the variable stored in the cell values, we named that variablerank.- This data is now tidy, but we could make future computation a bit easier by converting values of

weekfrom character strings to numbers usingmutate()andreadr::parse_number().parse_number()is a handy function that will extract the first number from a string, ignoring all other text.

billboard %>%

pivot_longer(

cols = starts_with('wk'),

names_to = 'week',

values_to = 'rank',

values_drop_na = TRUE

) %>%

mutate(

week = parse_number(week)

)# A tibble: 5,307 × 5

artist track date.entered week rank

<chr> <chr> <date> <dbl> <dbl>

1 2 Pac Baby Don't Cry (Keep... 2000-02-26 1 87

2 2 Pac Baby Don't Cry (Keep... 2000-02-26 2 82

3 2 Pac Baby Don't Cry (Keep... 2000-02-26 3 72

4 2 Pac Baby Don't Cry (Keep... 2000-02-26 4 77

5 2 Pac Baby Don't Cry (Keep... 2000-02-26 5 87

6 2 Pac Baby Don't Cry (Keep... 2000-02-26 6 94

7 2 Pac Baby Don't Cry (Keep... 2000-02-26 7 99

8 2Ge+her The Hardest Part Of ... 2000-09-02 1 91

9 2Ge+her The Hardest Part Of ... 2000-09-02 2 87

10 2Ge+her The Hardest Part Of ... 2000-09-02 3 92

# ℹ 5,297 more rows

# ℹ Use `print(n = ...)` to see more rows

> 🧠 What does parse_number() do?

It comes from the readr package (part of the tidyverse). Its job is to:

Extract numbers from a character string

✅ It keeps the number

❌ It removes all non-numeric characters (like “Week”, “wk”, etc.)

billboard_longer %>%

ggplot(aes(x=week,y=rank,group=track)) +

geom_line(alpha = 0.25)

scale_y_reverse()🧠 Why scale_y_reverse()?

Because Billboard chart rankings are reversed:

-

Rank 1 is the best

-

Rank 100 is the worst

We reverse the y-axis to make better rankings appear higher, which is more intuitive.

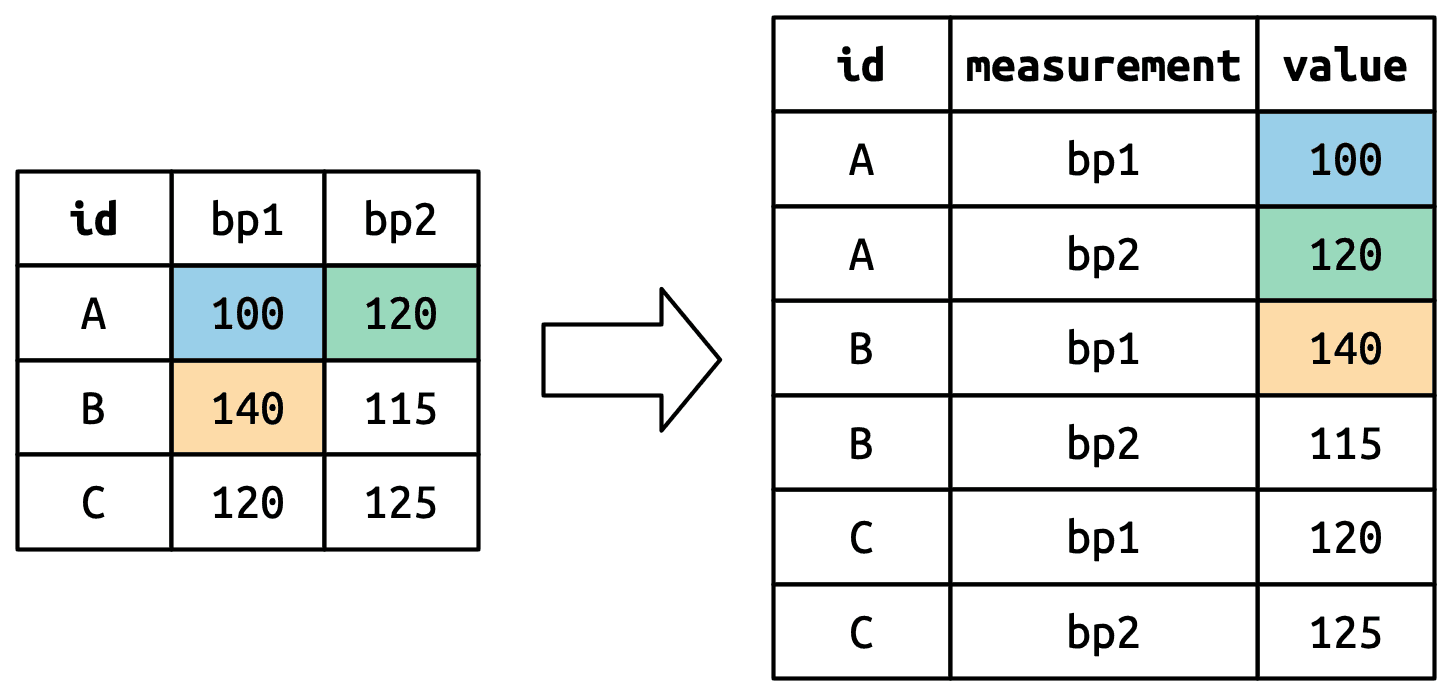

5.3.2 How does pivoting work?

df <- tribble(

~id, ~bp1, ~bp2,

"A", 100, 120,

"B", 140, 115,

"C", 120, 125

)

df %>%

pivot_longer(

cols = bp1:bp2,

names_to = 'measurement',

values_to = 'value'

)

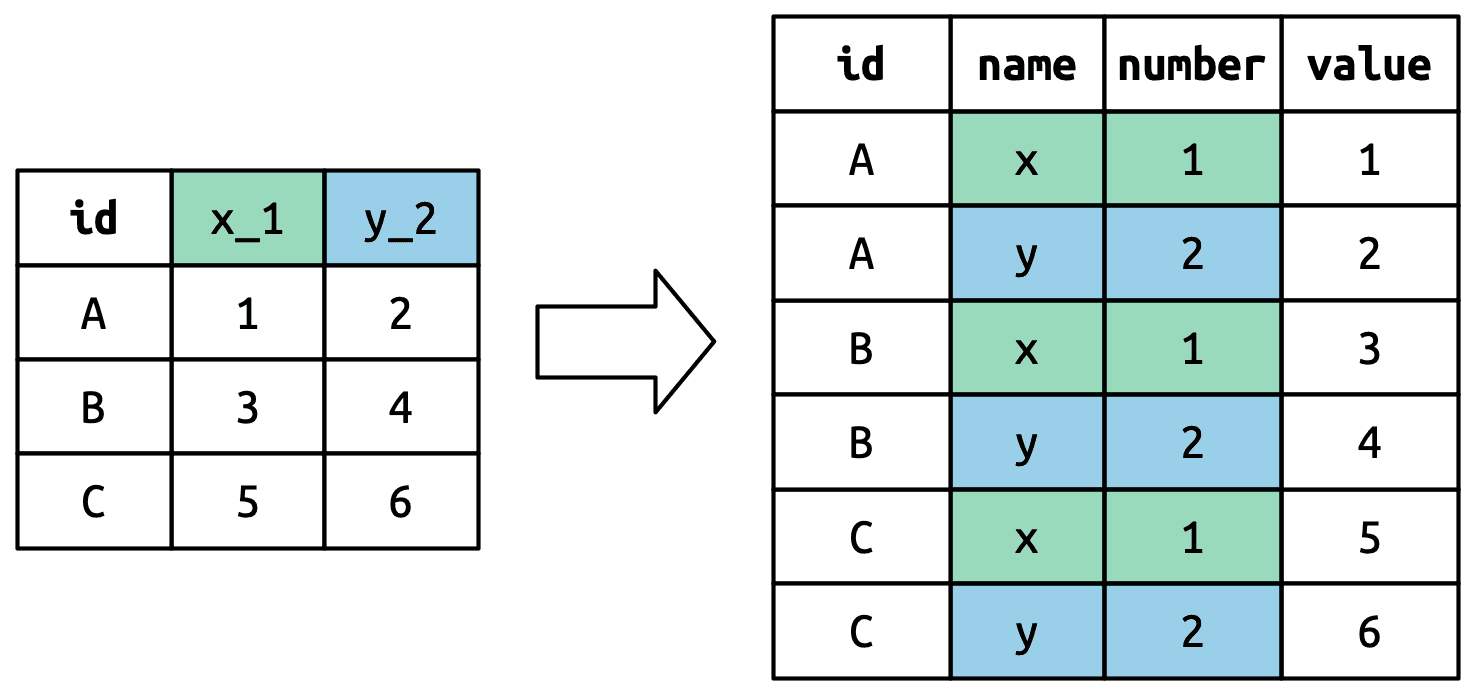

5.3.3 Many variables in column names

who %>%

pivot_longer(

cols = !(country:year),

names_to = c('dignosis','gender','age'),

names_sep = '_',

values_to = 'count'

)🔍 What does names_sep = "_" mean?

“When splitting column names into multiple variables using

names_to, split them wherever there’s an underscore (_).”

5.3.4 Data and variable names in the column headers

household

#> # A tibble: 5 × 5

#> family dob_child1 dob_child2 name_child1 name_child2

#> <int> <date> <date> <chr> <chr>

#> 1 1 1998-11-26 2000-01-29 Susan Jose

#> 2 2 1996-06-22 NA Mark <NA>

#> 3 3 2002-07-11 2004-04-05 Sam Seth

#> 4 4 2004-10-10 2009-08-27 Craig Khai

#> 5 5 2000-12-05 2005-02-28 Parker Gracie

household %>%

pivot_longer(

cols = !family,

names_to = c('.value','child'),

names_sep = '_',

values_drop_na = TRUE

)

#> # A tibble: 9 × 4

#> family child dob name

#> <int> <chr> <date> <chr>

#> 1 1 child1 1998-11-26 Susan

#> 2 1 child2 2000-01-29 Jose

#> 3 2 child1 1996-06-22 Mark

#> 4 3 child1 2002-07-11 Sam

#> 5 3 child2 2004-04-05 Seth

#> 6 4 child1 2004-10-10 Craig

#> # ℹ 3 more rowsI am confused about .value, so I asked Gpt to fully explain it to me:

🧠 First: What does pivot_longer() usually do?

By default, it takes many columns and turns them into two columns:

-

One for the column name (like

name) -

One for the value (like

Susan)

🌰 Mini example:

Original:

| id | name_A | name_B |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | Bob |

Usual pivot_longer() (no .value):

pivot_longer(cols = starts_with("name"),

names_to = "key",

values_to = "value")✅ You get:

| id | key | value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | name_A | Alice |

| 1 | name_B | Bob |

So everything goes into one value column — regardless of what type of data it is.

🤯 But what if… we had different kinds of variables in the columns?

Like in your case:

| family | dob_child1 | dob_child2 | name_child1 | name_child2 |Now the column names contain two pieces of info:

-

The type of variable:

doborname -

The child number:

child1orchild2

🧱 Option A: Without .value

pivot_longer(

cols = -family,

names_to = c("what", "child"),

names_sep = "_"

)Gives you:

| family | what | child | value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | dob | child1 | 1998-11-26 |

| 1 | name | child1 | Susan |

| 1 | dob | child2 | 2000-01-29 |

| 1 | name | child2 | Jose |

This is a long, stacked format. Everything is in one value column. You’d have to pivot_wider() again later to separate dob and name.

✅ Option B: With .value

pivot_longer(

cols = -family,

names_to = c(".value", "child"),

names_sep = "_"

)This says:

“Use the first part of the column name (like

dob,name) as the name of a new column, and the second part (child1,child2) as a grouping variable.”

Now you get:

| family | child | dob | name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | child1 | 1998-11-26 | Susan |

| 1 | child2 | 2000-01-29 | Jose |

Now it’s tidy:

-

Each row is a child

-

dobandnameare separate columns, not stacked

🎯 So why use .value?

Because you want different pieces of the original column names to become different columns, not all shoved under a single “value”.

With .value | Without .value |

|---|---|

| You get multiple value columns | You get one stacked value column |

| Easier to use directly (tidy) | Often need to pivot_wider() later |

| Each row = one observation (e.g. child) | Each row = one variable of one child |

5.4 Widening data

So far we’ve used pivot_longer() to solve the common class of problems where values have ended up in column names. Next we’ll pivot (HA HA) to pivot_wider(), which makes datasets wider by increasing columns and reducing rows and helps when one observation is spread across multiple rows. This seems to arise less commonly in the wild, but it does seem to crop up a lot when dealing with governmental data.

cms_patient_experience

#> # A tibble: 500 × 5

#> org_pac_id org_nm measure_cd measure_title prf_rate

#> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

#> 1 0446157747 USC CARE MEDICAL GROUP INC CAHPS_GRP_1 CAHPS for MIPS… 63

#> 2 0446157747 USC CARE MEDICAL GROUP INC CAHPS_GRP_2 CAHPS for MIPS… 87

#> 3 0446157747 USC CARE MEDICAL GROUP INC CAHPS_GRP_3 CAHPS for MIPS… 86

#> 4 0446157747 USC CARE MEDICAL GROUP INC CAHPS_GRP_5 CAHPS for MIPS… 57

#> 5 0446157747 USC CARE MEDICAL GROUP INC CAHPS_GRP_8 CAHPS for MIPS… 85

#> 6 0446157747 USC CARE MEDICAL GROUP INC CAHPS_GRP_12 CAHPS for MIPS… 24

#> # ℹ 494 more rowscms_patient_experience %>%

pivot_wider(

id_cols = starts_with('org'),

names_from = measure_cd,

values_from = prf_rate

)id_cols = starts_with("org")

This tells R:

“Keep

org_pac_idandorg_nmas identifiers — don’t pivot them.”

Because you don’t want org names or IDs turning into new columns — they should stay on the left, like “row headers”.

names_from = measure_cd

This tells R:

“Use the unique values in

measure_cdas the names of new columns.”

So CAHPS_GRP_1, CAHPS_GRP_2, CAHPS_GRP_3… become new column names.

5.4.1 How does pivot_wider() work?

I am confused by this sentence, so I ask gpt to explain it for me:

By default, the rows in the output are determined by all the variables that aren’t going into the new names or values. These are called the id_cols

🤔 So… what should stay as the “row identifier” (id_cols)?

The rule is:

Any column that is not involved in

names_fromorvalues_fromis used to group rows together — it defines one row in the new wide table.

In this case:

-

measurementbecomes column names -

valuebecomes column values -

So

idis left over → it becomes theid_colthat defines the rows

That means each unique id becomes a row in the result